The Bee's Knees

The concept of a lawn originated in medieval times, on the land outside European castles. The short grass enabled watchmen to see friends or foes approaching from afar. Over time, they became status symbols among the rich, influenced by 17th century France’s formal gardens of tapis verts, or green carpets. England quickly followed the fashion and from there colonists in the 19th century landed in the New World with the notion of flawless lawns as a symbol of wealth. Lawns remained a status symbol, taking a firm hold with the growing middle classes in North America. (Liz Primeau, Front Yard Gardens) And it continues to this day.

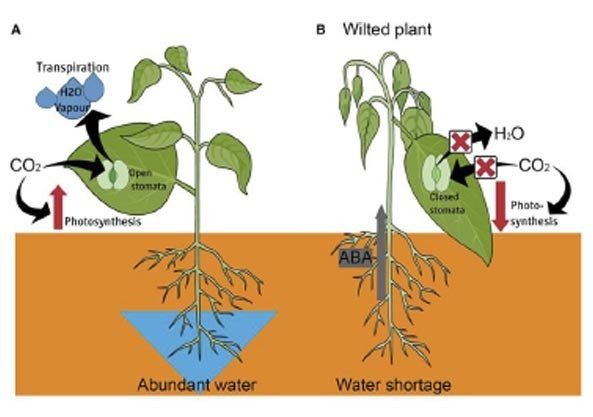

For many people, their lawn is a source of tremendous pride and the object of great care. But "turf" lawns are not naturally occurring plants — nor do they have the biodiversity science now tells us we need to provide helpful habitats for our pollinators. Those lawns may hold visual appeal, but they also have a significant environmental cost:

During the summer months, water usage in Canada peaks, and a half to three-quarters of all municipally treated water is used for lawns. To keep them looking their best, many of us have historically turned to pesticides and herbicides that contaminate soil, water, turf and other plants. Pesticide and herbicide run-offs into our waterways can also be toxic to fish and insects important to the ecosystem. (CBC News July 05, 2019)

Now, I have a push-lawn mower for the areas of grass growing in my backyard. I don’t feed that backyard or add anything to it – just mow it – and hey - it's all green. I’m not a grass-hater.

Lawns could act as carbon sinks — i.e., absorb more carbon than they release as carbon dioxide -if we’d just leave them be and mow them with a push mower. But we don’t. If you take into consideration the amount of energy that goes into producing fertilizer and fresh water, as well as power-driven mowers, well, lawns overall produce more greenhouse gases than they can take in. (ABC Science, https://www.abc.net.au/science/articles/2010/01/22/2799164.htm)

Plus, lawns lack biodiversity of vegetation when a diversity of plant life is just exactly what is needed for a strong and healthy ecosystem. Without diversity, pollinators, insects, birds and other wildlife have nothing to eat and nowhere to live. And that’s bad for us.

"Replacing lawns with native habitats is the best option," said Dr. Amanda Rodewald, a professor with the Department of Natural Resources and the Director of Conservation Science at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. And, she says, the best way to create a native habitat is by creating an alternative lawn.

There are excellent books available and information on-line about making changes toward a more biologically diverse (and healthy for us) ecosystem in your front yard. I have included some links at the end of this article to get you started.

What’s an example of an alternate lawn? Using plants that require little water – known as xeriscaping – to replace turf could be a change that can make a big difference to the environment – and your water bill.

Permaculture gardening means "permanent agriculture" and it is defined as working with natural forces—the wind, the sun, and water—to provide food, shelter, water, and everything else your garden needs besides plants and seeds. ... simply put, Permaculture gardening is a holistic approach to gardening. This may sound really daunting, but we have a group right here in Ontario to help with the transformation – big or little - of your garden into a more diverse and pollinator-friendly place for useful bugs and birds to visit.

In the Zone Gardens Project is a collaboration between Carolinian Canada and the WWF. Carolinian Canada’s network protects an incredible array of rare wildlife and natural treasures from Toronto to Windsor. The organization connects diverse Canadians to healthy landscapes and wild places of Canada’s deep south. WWF-Canada creates solutions to environmental challenges for Canadians.

I recommend you check out these helpful groups. I myself have registered my garden with them and I can tell you they are full of encouragement, tips and information on how you can modify your garden – by just planting a native plant or two – to tearing the sod up and starting right over.

Above: My own front garden (seen now in winter) crept out over the years:

I always saw the potential in it as an actual habitat for butterflies, birds, bugs, toads, and the odd snake – in the middle of a city. I sit on my verandah three out of four seasons enjoying the visitors to my bird bath, flowers, and sheltering trees. And in the winter, it provides seeds, rosehips, hollow stems for over-wintering bees, and sheltering shrubs by the bird feeder.

I hope you are inspired to look more deeply into this subject. We have the power to use our gardens for good.

Happy Gardening!

Some useful links:

https://www.plant.uoguelph.ca/trialgarden

Prepared by Grey County Master Gardeners for use by home gardeners and community groups.

For other use, please email

greycountymg@gmail.com

Latest Blog Posts