What's in a Name? Understanding a Plant's Botanical Name

For many people botanical names are intimidating, pretentious and difficult to pronounce. Common names on the other hand are familiar words, passed down from generation to generation and much easier to say. Especially among home gardeners the question is asked “Why do I have to know the botanical name?” In some situations the answer is “You don’t!” So, what’s in a name? Why should we pay attention to the botanical name? Two reasons:

Information! Information! Information!

A plant’s botanical name gives you specific information. Typically the colour, shape, surface texture or pattern, fragrance, bloom time, habitat or country of origin is revealed. The botanical name may also include the name of the person who discovered the plant or cultivated it. Or it might be commemorative.

World-Wide Recognition!

The botanical name is universal to all countries and languages. People travel. Plants relocate. Professional and amateur gardeners exchange information. The botanical name is precise and constant¹. There is no confusion as each plant has a specific name. There is no ‘lost in translation’.

Still not convinced?

In 2017 the Master Gardeners of Ontario (MGOI) led a movement to officially designate one plant as Canada’s National Flower. They came up with a short list of plants that are found across Canada and through an on-line ballot asked Canadians to vote. The winner was --- the Bunchberry!

Do you know what a Bunchberry looks like? Below are some images found from a Google image search using the word ‘Bunchberry’. Which is the Bunchberry that won the vote?

The botanical name for the nominated

Bunchberry is

Cornus canadensis. Below are the images that match

Bunchberry

Cornus canadensis. However, depending on where you live in Canada the common name is not always Bunchberry. In Ontario it is Bunchberry but in other parts of Canada it is the Canadian dwarf cornel, quatre-temps, crackerberry, or creeping dogwood. And in other parts of the world there are even more common names.

Common names cause confusion. Given that there are over 400,000 plant species in the world, it’s good that there is an internationally recognized naming protocol that records with certainty and accuracy the precise name of every plant.

Decoding the Botanical Name

In the 1700s, Swedish naturalist and explorer Carl Linnaeus developed a way to name and organize species. Simply put, he created a protocol based on a hierarchical classification system and that system has a two-part naming method (binomial nomenclature).² It was also Linnaeus who determined that names would be written in Latin as it was confirmed that any language in the world could translate the Latin words into their native language.

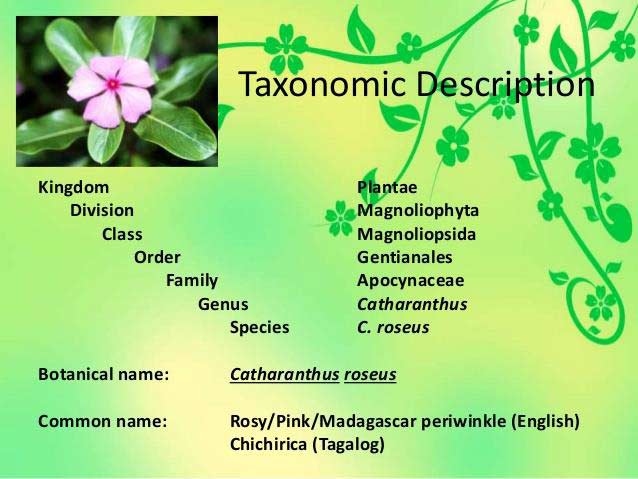

Taxonomic Description: Taxonomy is the science that finds, describes, classifies and names living things.

Gardener’s Latin

For gardeners the important details start at the word Family. Like a family tree, descendants are split into subfamilies. For plants a subfamily is called a genus. The genus can also be thought of as a category. The genus is a noun and the first word in the two-name binomial system. The second word in the two-name (binomial) is species. The species is an adjective which describes the noun.

Remember this two-name system was developed about 250 years ago; its utilization of Latin has since been adapted for modern-world users. Nowadays when looking at plant names a common phrase used is botanical Latin. For a few reasons we all know some Latin. The English language is partially derived from Latin. If you speak a bit of French, Spanish or other romance languages, you’ll know even more Latin. Perhaps you are of an age when Latin was compulsory in secondary school? All this is to say that by looking at botanical names you will also be reminded of word origins.

| genus » | genes » | genuine |

|---|---|---|

| rubra » | ruby » | red |

| pendula » | pendulum » | drooping or weeping |

| folia » | foliage » | leaves |

Remember the Cornus canadensis?

(Bunchberry)

| Genus |

|---|

| Cornus |

| species |

|---|

| canadensis |

In creating the two-name protocol. Linnaeus established that the first word (genus) would begin with a capital and the second word (species) would be all lower-case letters.

Cornus is a noun. It is Latin for horned, likely comparing the hardness of the wood to animal horn. Cornus ends in us which means it is masculine and singular. In lower-case

canadensis is an adjective that describes the noun, also masculine and singular. Canadensis is botanical Latin for Canada.

In addition to the genus and species, the naming of a plant may also include a commemorative name. Or, it might include the name of the person who discovered the plant or first cultivated it.

Clematis ‘Jackmanii’

Genus from the Greek klematis an old name applied to climbing plants. Cultivar named after the 19th-century British nurseryman, George Jackman.

If you’re ready to start learning some botanical names there are plant characteristic charts in both botanical Latin and English. There are also several user-friendly plant dictionaries and websites for gardeners that convert the common name to botanical name or vice versa. A few are listed under References & Suggested Readings. Below are examples of the chart format from two websites.

| Colours | Habitat | Form |

|---|---|---|

| alba » white | alpinus » alpine | contorta » twisted |

| azur » blue | maritima » seaside | globose » rounded |

| Leaves | Flower Type | How it Grows |

|---|---|---|

| aquifolium >> pointed leaves Ilex aquifolium >> common holly | centifolia >> 100 leaves/petals Rosa centifolia >> cabbage rose | arboreum >> tree-like Aeonium arboretum >> tree houseleek |

| Ilex aquifolium >> common holly | maritima >> seaside | globose >> rounded |

The hardy, disease-resistance and spectacular blooming daylilies do not belong to the genus Lilium (Lily). The genus for daylilies is hemerocallis. The word hemerocallis means ‘beautiful for a day’. And they are!

Botanary⁶ (davesgarden.com) is an excellent website to quickly find the meaning of a Latin word.

-

Hemerocallis 'Dancing on Air'

Photo By: John DoeButton -

Hemerocallis 'Chicago Knockout'

Button -

H. 'Chicago Knockout'

Button

Another way to learn the botanical name is to read the story behind the name. Books like Bill Neal’s Gardener’s Latin give you the history and the ‘lore’. How did the Heliopsis helianthoides (False Sunflower) get its name? Who named the Hydrangea quercifolia (Oakleaf Hydrangea) and why name a hydrangea after an oak tree?

What’s your favourite plant? What is your must-have 2018 plant? Find out its botanical name and decode its binominal name. Who discovered it? What does the name tell you about its characteristics and origins?

Spell it out! Say it out loud! Enjoy the name!

References & Recommended Readings:

¹The introduction of DNA to identify and classify plants has resulted in some changes and more changes are possible. “Gardeners Latin classed plants according to structure, originally what could be seen with naked eye, then microscopes of increasing strength and now DNA. DNA is shaking up the botanical tree!” Ursula Karalus,MG

Ursula recommended reading:

Why Plant Names Change: A plant’s botanical name is more than just a label! (Friends of the Garden Daily News)

The Father of DNA Barcoding: Professor Paul Hebert, Department of Integrative Biology, U. of Guelph

²Carl Linnaeus, ‘Father of Modern Taxonomy’ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Linnaeus

³ Carl Linnaeus (photo and caption)https://en.wikipedia.beta.wmflabs.org/wiki/Carl_Linnaeus

⁴Botanical Nomenclature Guide: The Meaning of Latin Plant Names

https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/garden-how-to/info/latin-plant-names.htm

⁵Botanical Terms and their definitions

http://www.wildchicken.com/nature/garden/ga007_botanical_words_and_definitions.htm

⁶Searching Botanary

https://davesgarden.com/guides/botanary/search.php?search_text=clethr

Dictionaries

Coombes, Allen J. Dictionary of Plant Names, Timber Press, Portland, Oregon 1995, ISBN: 0881922943

Language Gardeners Speak: Naming Plant Name (excellent quick reference)

Harrison, Lorraine, Latin for Gardeners, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois 2012 ISBN – 13: 9780226009193 (over 3000 plant names, plus explicit drawings and some ‘stories’)

________________ Horticulture - Plant Names Explained: Botanical Terms and Their Meaning,

Horticulture Publications, Boston, Mass, 2005 ISBN: 1558707476 (plant name plus some history and stories)

Hodgson,Larry, How to Remember Botanical Names (Canadian!)

https://laidbackgardener.blog/2015/01/27/how-to-remember-botanical-names

Roach, Margaret, Decoding Botanical Latin

https://awaytogarden.com/decoding-botanical-latin

Yoest, Helen, Decoding Botanical Latin

http://gardeningwithconfidence.com/blog/2014/12/20/decoding-botanical-latin

Pronouncing botanical Latin names often flusters and intimidates people. First remember that we are used to saying some names e.g. trillium, clematis, geranium, crocus, hydrangea.

“Courage is the best principle: just have a go. Say the word aloud several times to hear how it sounds. In most cases the stress is placed on the second or third syllable. There is often no wrong or right way: ask tree taxonomists and you may well get three different versions. Never mind: we can all enjoy saying ‘silly bum’ for Silybum marianum, the milk thistle.”

Jane Sterndale-Bennett, Plant Names Explained

Prepared by Grey County Master Gardeners for use by home gardeners & community groups.

For other use, please email greycountymg@gmail.com February 2018pdw

Latest Blog Posts