Does a Plant Make Sense of the World?

In 1964 Dorothy Retallack published a book about how plants respond to music called “The Sound of Music and Plants”. She asserted that plants grow better when exposed to Mozart than when they are blasted with rock music. Her book was very popular and was instrumental in encouraging the idea that we should all be singing to our plants. Although her findings were eventually disproved, her ideas were part of a long standing scientific enquiry. Are plants sentient? What do they feel? What do they know? Are plants conscious?

First, I must confess that whenever I think about this topic I am reminded of the book “The Day of the Triffids”, a classic sci-fi book written by John Wyndham in 1951. In the story large dangerous plants become mobile and terrorize humans, who have been blinded by the same phenomena that gave the plants mobility. To make matters worse, throughout my childhood my father always referred to large weeds in our yard as triffids. That may

explain why I get a little anxious when I consider that my garden is watching me. New paragraph

Are my plants watching me? There is no doubt that plants sense light – both in intensity and in different wavelengths or colours.

We observe this clearly in our houseplants sitting on the windowsill. The plants turn and grow towards the light – a phenomenon called phototropism. It was Charles Darwin who showed that this is due to the plant responding to light using sensors in the tip of the growing shoot. A contemporary of Darwin’s, Julius Von Sachs, showed in 1864 that it was blue light that stimulated the plant to grow in a particular direction.

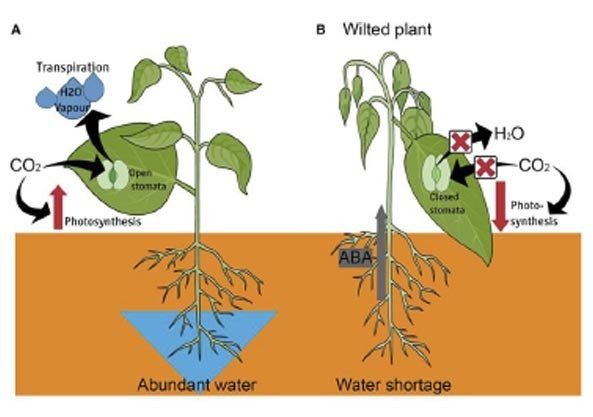

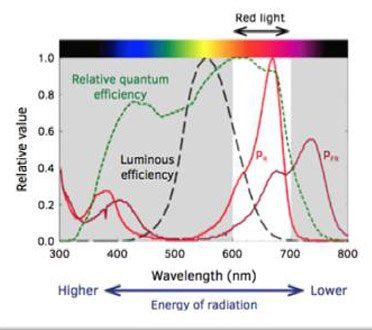

Plants also respond to different colours of red light. Growth and flowering depend on the length of darkness, not on the length of day light, and can be influenced by exposing plants to light in the middle of the night. Plants sense bright red (think sunset) and far red (think dawn) with phytochrome, a photoreceptor. Plants determine the time between sensing these two colours, i.e. - the length of the night, and therefore know when to flower or set seed. Commercial growers use this response to influence blooming periods for retail purposes.

These are just two examples of how plants sense light. There is no evidence that plants see the way we do - they do not coordinate the light information they receive and put together a picture of the world around them – but certainly we would say they have a rudimentary sense of the light in their immediate environment.

Can plants hear? Do they benefit from us singing to them or suffer when exposed to too much noise? Using rigorous scientific enquiry Mrs. Retallack’s theories were disproved, plants do not ‘hear’. There is some evidence that they are sensitive to vibration however – which means you would have to sing very loudly to have an impact.

Plants do sense touch, there is no doubt. Botanists have clearly proven that touch has a negative effect on plant growth. They have coined a fantastic word for this process: thigmomorphogenesis. We see this occurring in plants exposed to natural touch in the environment – trees growing straight and tall in a valley and the same species stunted and misshapen in areas exposed to strong winds. This makes sense as an adaptive process that ensures survival – a short stunted tree is less likely to be blown over than a tall one.

In a laboratory setting, plants touched everyday were stunted and flowered later than those left alone. So, the moral of this story is – sing all you want (they can’t hear you anyway) but don’t ever pet your plants.

Plants also respond to touch in other ways, through mechanoreceptors. A vine will grow more rapidly when it touches something it can cling to, allowing it to climb higher and reach more light. A Venus Flytrap will snap shut when an insect trips over its mechanoreceptors, allowing it to trap the insect and reach more dinner.

Finally – do plants smell us as we are smelling them? Can they detect scent?

When we smell something we are picking up complex chemicals released by the object we are smelling. These volatile chemicals are picked up by special receptors in our noses and translated by our brains to have a specific meaning such as “This smells delicious, I want to eat this”.

Plants do something very similar. We are all familiar with the practice of putting a ripe apple in a bag with other fruit that we want to ripen. Apples release the chemical ‘ethylene’ and the other fruits pick it up, which stimulates them to ripen too.

Plants also communicate through the release and detection of chemicals. For example, a tree under attack by an insect will release a chemical that nearby trees will detect (i.e. smell). The receiving trees then adapt to protect themselves from the invading bug, for example, by increasing the concentration of tannic acid in their leaves, making them unpalatable.

This is just a sampling of the fascinating ways that plants sense their environment. For more information, I recommend the book “What a Plant Knows” by Daniel Chamowitz, or the free online course of the same name on the Coursera web site. Most of the information in this article comes from these sources.

To definitively answer the question – are plants conscious? - we need more study and scientific knowledge. Currently, it seems highly unlikely that plants have a conscious awareness that is in any way similar to ours.

This is somewhat reassuring for those of us who have read “The Day of the Triffids”, but still I suggest you do not read it if you want to continue to feel safe and secure amongst your sunflowers.

References:

Wydnham, John The Day of the Triffids, first published 1951 ISBN: 0812967127

Chamowitz, Daniel What A Plant Knows: A Field Guide to the Senses, first published 2012 ISBN: 0374288739

Understanding Plants – Part 1: What a Plant Knows

https://www.coursera.org/learn/plantknows

¹https://gpnmag.com/article/red-light-and-plant-growth/

Photo credits: photos were found through a google image search.

Additional Reading:

If you enjoyed this topic you may also want to read

The Hidden Life of Trees, Peter Wohlleben, first published 2015 ISBN: 9781771642484

Latest Blog Posts